The maker of champions –

Thoughts and tales by Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer

The riding instructor died at the age of 88 in October 2014

The last interview with the “Doctor” as he was called everywhere

At the beginning of December 1998 visitors arrived from Warendorf in a double-decker bus, laden with members of a promotion club for riders. Their aim was to stand beside Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer and watch him during training. Not everybody was allowed to look over the “Doctor’s” shoulder and listen to his usually curt directives. Here, too, he was particular. And he hated nothing more than his concentration being disrupted.

At tea-time someone suggested that you simply had to be rich to build and maintain such a facility and to buy such horses. Schulten-Baumer replied: “I have never been rich. I come from a simple background. But as a very young boy I was already crazy about horses. I groomed horses on the neighbouring farm to be allowed to ride.” And he continued chatting: ”You have to want something in life. I have always been besotted with horses, I always wanted to own my own stables and horses and get to the very top in the sport. I consistently pursued that aim, even though I sometimes thought I couldn’t go on.”

Uwe Schulten-Baumer was born on a farm near Essen. He was a single child. One afternoon he and his parents were invited to a riding event accompanied by music. It turned out to be a key event in the life of Uwe Schulten-Baumer. The riders in tailcoat, plastron and bowler hat were the elegant part, afterwards the youngsters could jump over a small course. From then on he kept on and on until he was allowed to ride a horse. He received his first instructions at a small riding stable near his primary school where in return he groomed and watered the horses before school and helped mucking out. He was just twelve years old. And he had his first professional goal in his sight: riding instructor. At the tender age of twelve he began an apprenticeship at the Riding and Driving School Leer in Lower Saxony, not far from Emden on the North Sea coast, but far from home. His first experience on the way there may have shaped his eventual passion for the swinging back, for the totally supple horse. Schulten-Baumer: “I was picked up at the railway station with a carriage and pair. I am still seeing the swinging backs of the horses in front of me, something I love about horses and like to remember.”

He was in the war for six months, on the cruiser “Nuremberg” in the Baltic Sea. He was released from captivity in May1945, became a commercial apprentice in the steel industry, caught up with his university-entrance diploma, studied economics and received his doctorate with a study about costs in the cement industry. He got a job as managing director in Duesseldorf. And in the evenings he could ride a lighter horse than the cold-blooded animals preferred in agriculture. The mare’s name was Senta and she had a talent for jumping. Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer rode her at the first international tournament in Aachen after the Second World War in 1949, finishing third in the puissance and seventh in the Grand Prix.

What did you learn from you beginnings as a rider?

“You may not overstrain horses, they would lose their elasticity. And I found out that you have to make sure when buying horses that they have excellent basic gaits: walk, trot and canter.”

Profession, horses, trainer – how did you achieve that?

“It was stress. Sometimes I travelled to and fro between office and tournament venues. It wouldn’t have been possible without enthusiasm. That’s why I always maintain: You can’t exercise this sport without blind passion – and you have to persevere.”

How was it with Nicole Uphoff and Rembrandt?

How was it with Nicole Uphoff and Rembrandt?

“First of all I want to emphasise that as a trainer you also have to attune to the respective horse. There are no templates. Nicole came with a horse that sparkled but his entire musculature wasn’t right; the horse had a thin neck, and you had to respond to the animal’s temperament. The horse tended to shy away from something, and then was punished. That led to the shying away getting ever worse, for the horse was not only scared of an unknown obstacle but also of the entailing punishment. Therefore the horse could no longer be ridden in tournaments. When facing an object he might shy away from I advised Nicole to tap the horse on the neck and loosen the reigns in order to give him the opportunity to first look at the object or obstacle. And the second advice was to ride the horse deep so that it began to swing easily via the back. Rembrandt’s eventual strong point was his suppleness. We didn’t train piaffer and passages according to the old, well-known method with stick, whip and spurs but trained everything flowingly without ever losing the rhythm. That’s how the later well-known wonderful transitions were achieved. The piaffer has never been ideal because the horse was limited in the foreleg, but the judges gave good marks because Rembrandt executed the tasks effortlessly. But all that had first to be recognised by the judges too, and the Swiss judge Niggli was the decisive person, who once said to me: We all want to get away from forced riding…”

Wolfgang Niggli, judging, wasn’t that a real change in dressage?

“It certainly was the end of heave-ho riding with whip and spurs. Niggli also once told me that we should stop that trend because we want to have relaxed and supple horses. All that also referred to other tasks such as half-passes and passages. About Rembrandt I would like to add: This horse’s distinctive feature was the effortless movement. I would probably have considered purchasing Rembrandt if offered, not because of the yield of movement but because of the effortlessness.”

The world likes to talk about the classic riding method, and you?

“I think there is no classic method, for it then should have been valid for decades or even centuries. Every time has its own classic method. But everything changes. The experiences with horses collected in the past, right or wrong, everything concentrates in today’s perceptions. The classic method is changeable. Riding according to the classic method cannot be looked up. We ultimately want to have a horse which progresses ideally according to its physical capabilities.”

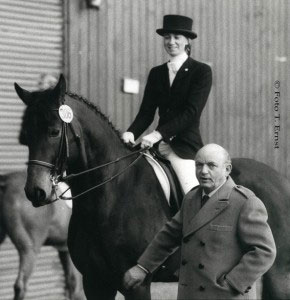

Dr. Uwe Schulten Baumer mit Isabell Werth / Foto: T. Ernst

Principles at tournaments…

“It is important that the horse is never scared by a task. Many riders make the big mistake to punish a horse with a sharp halt after an error. Then it is all tensed up in the next task. The horse must understand what the rider wants. It is also important to praise the horse after a successfully completed task. When working with horses you should keep in mind that the soul of the horse also has to contribute. Unfortunately that’s often forgotten. Take care that you look rather for your own mistakes than for that of the horse. A horse should never be overcharged, neither mentally nor physically.”

What roles do the smith and feeding play?

“The smith is very important. It is similar to people: If the shoes don’t fit, you can barely walk. Feeding replaces some curry comb. Horses should be top athletic and have no deficiency symptoms.”

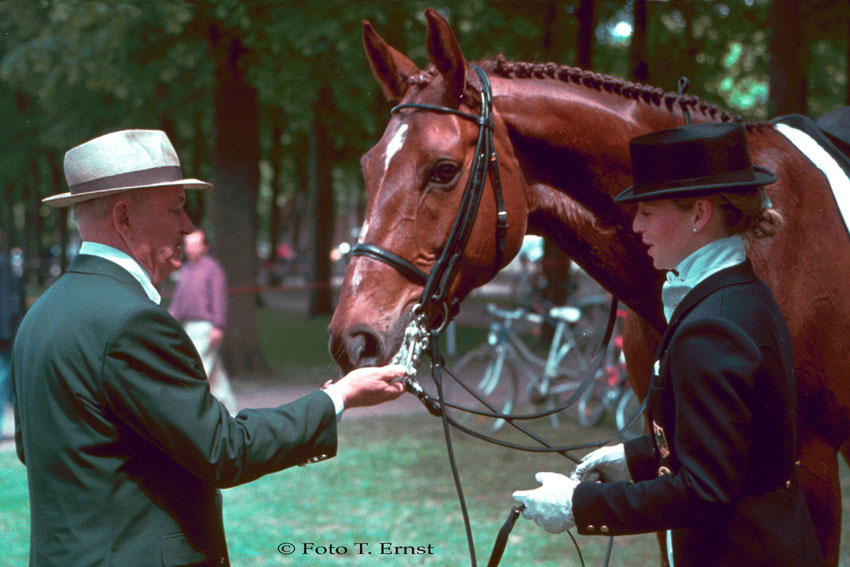

Gigolo is considered the most successful dressage horse…

“Gigolo certainly wasn’t the model for a statue. But the moment the gelding moved he radiated power, elasticity and drive, perfected by his motivation.”

What do you expect from a judge?

“I expect from a judge that he judges in all conscience, unaffected by what has previously been said, unswayed by the risk to be wrong. In my opinion it is also important that a judge should be capable of competing himself in the event. This should at least facilitate marking.“

And how should a rider behave?

“Judges are also human beings, and very sensitive ones. First of all the rider should be self-critical, but should certainly enquire in a normal tone, what was good and not so good in his performance, what a judge wants to see from a horse and what he doesn’t want to see.”

Dieter Ludwig – Übersetzung Ingeborg Kollbach

Der Doktor und Isabell Werth mit Gigolo / Foto: Tammo Ernst